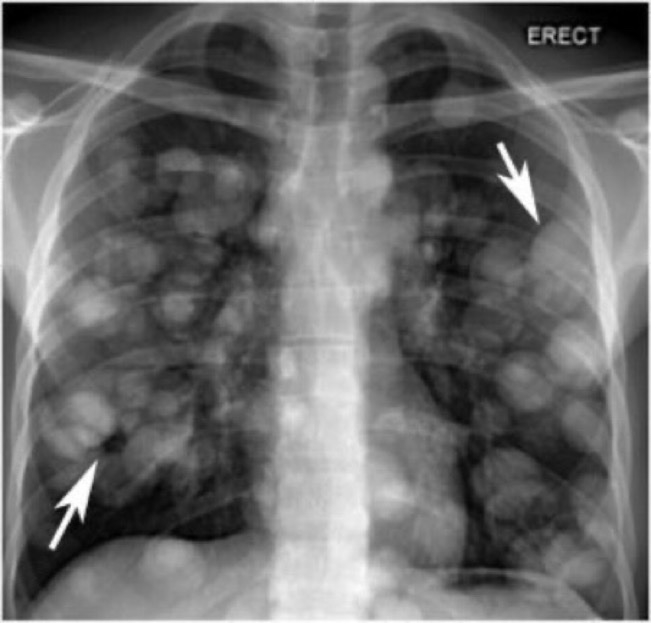

History: A 56 year old female presented to ED with 1 episode of GTC seizure. Neurological examination was normal except for postictal confusion. NCCT brain showed multiple calcified granuloma, some showing perilesional oedema in the frontal, parietal & occipital lobes. Routine CXR showed typical rice-grain-shaped calcification in the chest wall muscles. Xray thigh and forearm were ordered which showed similar lesions. What’s the diagnosis?

Answer: Rice grain calcification is characteristic of infection with Taenia solium (cysticercosis); when the inflammatory response of the host kills the larval cysts (cysticerci), they undergo granulomatous change and become calcified. Demonstration of rice-grain clacification on plain radiograph is a minor diagnostic criterion for neurocysticercosis (NCC). Their presence support NCC as the cause of ring-enhancing lesions in brain imaging.